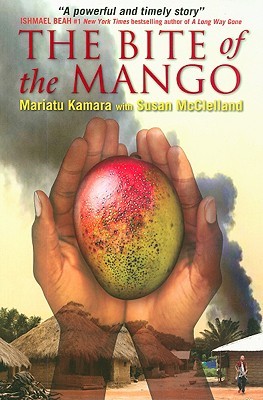

The Bite of the Mango

The Bite of the Mango

Mariatu Kamara with Susan McClelland

Reviewed by Emily Gillespie

In the autobiography The Bite of the Mango, written by Mariatu Kamara with Susan McClelland, Mariatu shares a revealing first-hand account of her experience of violence during the conflict in Sierra Leone. Mariatu, along with several other youth have their hands cut off by child soldiers. This novel provides an account of Mariatus experience of becoming disabled, her communitys displacement by war, and her eventual new life in Canada. It is hard to critique a narrative that is an intimate first person account. However, The Bite of the Mango is a holistic description of one persons experience with disability against the backdrop of war, politics, poverty, and colonial history. It is told from the refreshing perspective of youth, and combines intelligent reflection alongside a childs confusion about the events taking place. The text is written using an accessible vocabulary, and as a person who is unfamiliar with the history of Sierra Leone, the text is clear. Mariatu tells her story in a compelling way, balancing the horrific details of the conflict, with her story of resilience and communal strength.

I am thankful for the intensely personal details of her experience with disability, against the backdrop of academic theorizing that often fails to adequately consider individual experience. This first-person account offers insight about local and global disability politics, and how people may experience disability in relation to other intersectional identities, again reminding the reader that there is not a universal experience.

Mariatus story displays a complex account and critique of gender roles in Sierra Leone. She refuses to represent herself as a passive victim of either gendered violence, or the war; rather, a narrative of self-determination emerges. For instance, she challenges the idea of marrying the man she is told she will marry and resists his advances. Mariatus account of sexual assault, and subsequent childbirth, display her childlike confusion over what happened, combined with a denaturalization of motherhood, as she struggles to love her baby. It is worth noting that while she acknowledges that both males and females have limbs amputated by the rebels during the war, it is females who are given the opportunity to go overseas. As a young female with a disability, Mariatu is still encouraged by her family to attain an education, and help support her relatives; this suggests the value of girls in this community.

The term Temporarily Able-Bodied (TAB) is a familiar phrase in disability politics. It suggests that being able-bodied is temporary, and that disability rights and activism is relevant for everyone, because if people live long enough, will all experience disability. Often in western discussions of being TAB, the threat of disease and age is explored, but for Mariatu, her healthy body becomes disabled through an act of political violence. Mariatu is told that they will cut off her hands, to make a political statement to the president and because I dont want you to vote (40). This shows the political context of bodily violence she and others experienced, and the literal and figurative suggestion that people with disabilities have less of a vote and voice in society. However, Mariatu, along with her friends in a theater group, challenge the assumed voicelessness that the rebels associate with disability by finding ways to address their experiences with war, and celebrate life, even in a refugee camp. The rebels suggest that it is better to be dead, than live without hands. Mariatu briefly echoes this sentiment, but eventually challenges this as her story becomes one of her new experience with her body and resilience. This account of the politics of becoming disabled allows for further discussion about what it means to become disabled not through nature, but through violence, be it at the hands of rebels, governments or intimate relationships.

The underlying theme that emerges in this account is resilience which is liberating against the common social narrative of disability as equating to tragedy. Rather than showing disability as weakness, Mariatu explains the struggle for her survival after her hands are cut off. For instance, she tells of walking a great distance by herself for medical help. This is not a western account of disability, where medical help is readily available after an accident, highlighting the particular experience of becoming disabled during the war in Sierra Leone.

Karma explains her struggle to adapt to her modified body, but also shows that she is not alone in this process, other youth are also adjusting to life after the violence of war, and she is supported by her community. This is a story of self-determination; Karma repeatedly has insight into her needs and trusts her self-knowledge. For example, when she arrives in England, she rejects the prosthetic hands, explaining that she already has an efficient system of using her arms for self-care. Karma explores the importance of telling ones story. In Canada, she is frustrated by journalists misrepresentation of her experience and writes a first-person account. Mariatu repeatedly challenges the idea that other people, including adults, know more about her needs and experiences.

This is a compelling work that engages with the complexities of youths experience with war, and the interplay between those experiences and disability. Mariatu at times is frustrated by her circumstances, but tells a story of survival, and highlights the importance of fostering a place where people with disabilities, and people in African countries, have the space to define their own experiences and needs. The only shortcoming of the book is one that is shaped by the page number and the lack of details about the other youths comparative experiences of disability, and her relationship with her family in Sierra Leone once she comes to Canada. I am also left wondering what the journalist Susan McClellands role is in creating this work. Overall, this is a powerful narrative that uses personal experience to challenge the narrative of children as passive victims of war and I would highly recommend it.

Kamara, Mariatu, and Susan McClelland. The Bite of the Mango. Richmond Hill: Annick Press Ltd., 2013: Print.